Should Independent Schools Partner with State?

By

8 years ago

If independent schools are charged by a government green paper to help change the state sector, then heads need to know it’s a two-way street, says Keith Budge

Keith Budge, chair-elect of the Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference (HMC), shares his thoughts on the most recent government green paper for schools.

Last summer, The Guardian ran a story on the sponsorship of state comprehensive schools by independent schools. It asked whether there might not be a better way to do it than has been done so far and focused on the recent efforts of Wellington College to take over the Wellington Academy. The article cited this as an example of ‘a prestigious private school taking over the running of a challenging academy’, in response to former schools’ minister Lord Adonis’ 2007 imperative that the independent sector should do more to implant its ‘educational DNA’ into state schools through sponsorship.

This expectation is repeated in the government’s latest education green paper, Schools that work for everyone. The paper calls for ‘independent schools to spread their expertise through the state system’ for the benefit of ‘ordinary families’, particularly the so-called JAMs – those ‘just about managing’.

It appears that the Wellington Academy takeover has been a bumpy ride, with changes to both staffing and curriculum sparking student protest. If, as The Guardian suggests, Wellington has struggled in its efforts at academy sponsorship, it does not appear to be alone. Of the few academies established under such arrangements, a significant proportion have received Ofsted reports that are less than glowing.

Purpose of the government green paper

However well-intentioned efforts might be on the part of independent schools to partner state schools, the undertaking can never be the simple transplanting of what works well in one educational setting into another. I am regularly asked what lessons from the Bedales experience we might offer to other schools, and I am always reticent.

I know what works for us at any particular point in time, and while I have ideas about what constitutes good education as a whole, I am mindful that context is everything. I would be wary prescribing from a distance what would work in any another independent school as I would be for a state comprehensive.

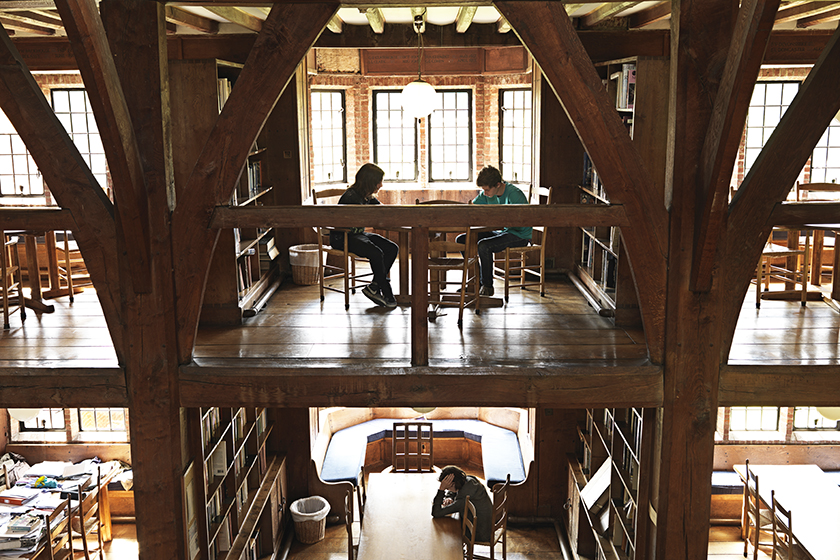

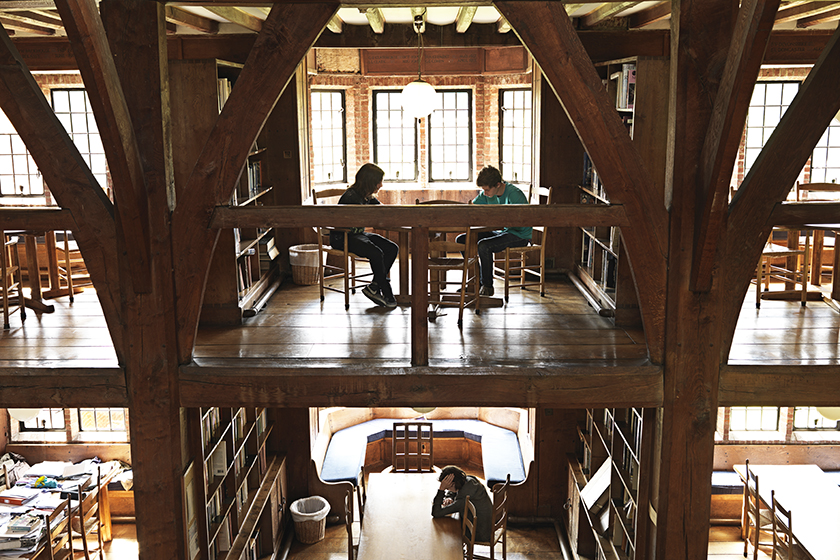

By way of example, Bedales sits at some remove from many independent schools in that we do not admit students on the basis of academic merit alone. Rather, we admit young people who we think might be suited to our ethos, are willing to work closely with our teachers and can access the curriculum. Our approach to admissions means that we can ensure, as far as we are able, that students will be amenable to our ways of doing things, which is the case, to some extent, with all selective schools, irrespective of their purpose and culture.

Indeed, we are reliant on our student body to help us continually reassess our way of doing things. Does it work for us? In a nutshell, yes. While we look to outside sources for inspiration, we do so critically and with an eye on our own cultural make-up. In recent years we have commissioned research on the relationship between our approach to teaching and learning and our student’s academic appetite. This is no wholesale importation of ‘best practice’, but rather the stimulus for an informed reflection on what we do and how we do it.

How do school partnerships work?

So how might the transplanting of a context-specific independent school ethos to a state comprehensive school work in practice? A seminal sociological study in 1969 by Jackson and Marsden, Education and the Working Class, explored the educational experiences of working class young people attending a grammar school in Huddersfield. It articulates the clashes of neighbourhoods and school cultures, of rules and behaviours, and expectations. All of these young people had demonstrated the academic potential to thrive at grammar schools, but for various reasons associated with cultural dissonance, many of them struggled to bridge the divide between home and school.

I’m not suggesting that this applies in the case of Wellington Academy. However, it is pertinent to ask whether we can reasonably expect cultures, structures and practices developed around the appetites of – for the most part – privileged children with their associated cultural baggage to always work for those for whom education may have rather different connotations.

Does this suggest that efforts on the part of independent schools to help state schools in their efforts to transform themselves are doomed? Certainly not, and I know my view is shared by many of the independent schools who are successfully working in partnership with state schools. But there is an important caveat. Such arrangements must be bilateral – it is wrong to place faith in the idea of a simple flow of know-how from the independent to state sector when there is much to be learned from a return flow.

A successful partnership

At the behest of the Times Educational Supplement, I took part in a mutual job shadowing exercise with Geoff Barton, my opposite number at King Edward VI comprehensive school in Bury St Edmunds. I spent a day with him on his patch, and he a day with me on mine. I learned a great deal from the experience and was struck by the realisation of how little I really knew of his world. My admiration for his work and that of his staff for achieving what they do under the shadow of Ofsted was considerable. There are things they do that we could learn from – for example, their exchange scheme with a school in Shanghai, which has been made integral to their student leadership programme, and their use of data tracking. I know that Geoff was similarly struck by some of our work at Bedales.

Indeed, it was this exercise that gave rise to our emerging idea that a reframing of the discussion of partnership between schools of all stripes might be warranted. As educators in our various settings – state or independent, selective or non-selective – there is far more that unites us than divides us, and we have much to learn from each other despite our rather different governance arrangements. What we learn and how we learn it is another question.

The Education Green Paper sets out the need to widen opportunity and to raise standards in maintained sector schools. In the case of Bedales’ contribution, I see further scope to bring our expertise and facilities to bear to support those enriching subjects that we are strengthening – think art, design, drama, dance and music – and yet find themselves outside of the English Baccalaureate and hence at the bottom of the state school curriculum pile.