Heads Debate: Coed vs Single Sex

By

4 years ago

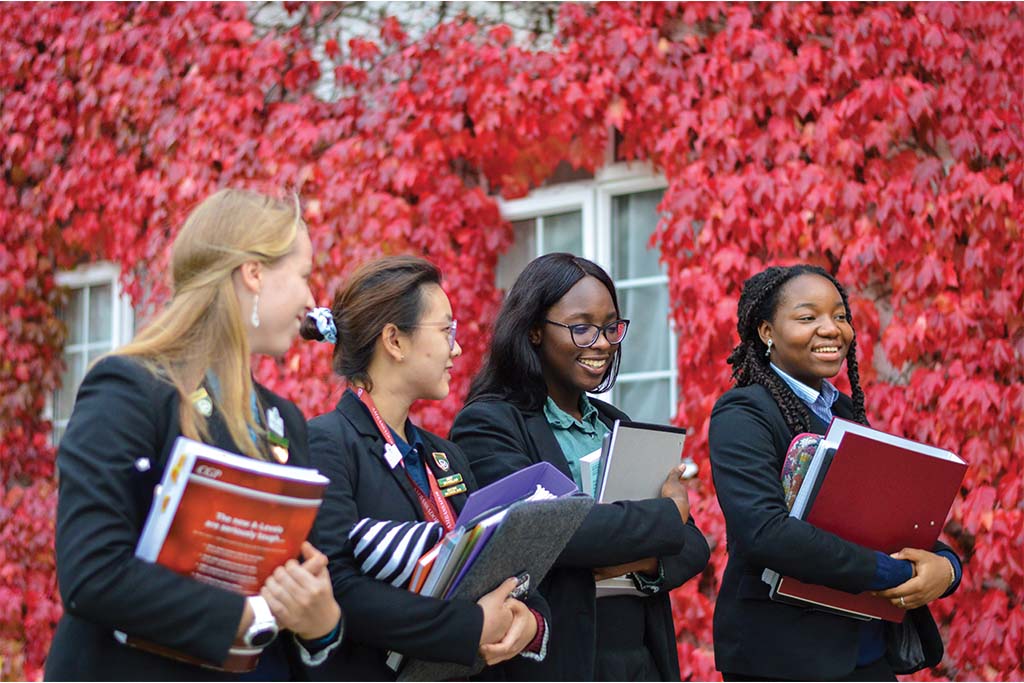

As Winchester College welcomes girls into its sixth-form, Eleanor Doughty finds that heads are divided on the future of single-sex education

On Tuesday 21 December 1869, Edward Thring, headmaster of Uppingham School in Rutland, convened a panel of 13 headmasters at his house. These heads – of Repton, Felsted, Oakham et al, all single sex boys senior public schools – went on to form what is now known as the Headmasters and Headmistresses’ Conference (HMC).

Now only three of the founder member schools remain single-sex – Sherborne, Tonbridge and Dulwich College. It’s a familiar story. Of the 18 members of the Rugby Group, also all former boys’ schools, just two remain boys-only without plans to admit girls. This September, 13-year-old girls arrived at Charterhouse for the first time. Winchester College is opening its sixth-form doors to girls next year after 640 years of being boys only.

Today, the HMC has 298 member schools. Just 48 are boys only. In contrast, the Girls’ School Association (GSA), whose senior girls’ member schools are also part of the HMC and include the 23 Girls’ Day Trust schools, has 142 members. So what happened to the boys’ British public school?

The first one to break ranks was Marlborough College. The Duchess of Cambridge’s alma mater took the decision to admit 15 sixth-form girls in 1968. Where one goes, others follow: Rugby in 1970; Uppingham and Brighton College in 1973; Stowe in 1974, St Edward’s, Oxford, in 1982 and Oundle in 1990. By the mid-1980s two-thirds of boys’ public schools had female pupils. Speaking at a 1984 conference, Peter Watkinson, headmaster of what is now Rydal Penrhos School in North Wales, described the admittance of girls into his own school as a ‘survival tactic’. It had, said Watkinson, ‘enabled a large number of boys’ schools to ride… the rough waves of unprecedented inflation and political hostility’. In short, teenage girls of the 1980s saved the public school.

Dr Martin Stephen, the former High Master of St Paul’s, with his wife Jenny, a former head of South Hampstead High School, was the first housemaster of St Alban’s, the first girl’s house at Haileybury in the 1970s. Dr Stephen wishes that the obvious conclusion, that co-education often came about for financial reasons was more openly admitted. ‘The motivation for bringing girls in was firstly financial, and secondly league table-dominated,’ he says, adding that, ‘I’ve never seen any shame in bringing extra pupils in because you need to address the balance sheet and improve the results. Just be honest about it.’

Co-education has been – and continues to be – a boon to the public school with many dipping their toe in gently by first just taking girls in the sixth form. But not everyone believes that this is a good model. Half a century after the arrival of its first sixth form girls, Charterhouse is going fully co-ed this year. ‘The days of boys’ schools with girls only in the sixth form are gone, I think,’ says Dr Alex Peterken, Charterhouse’s headmaster. ‘If you’re going to do co-ed, do it properly.’

I wonder why it took so long for this to happen at Charterhouse. ‘There was a feeling from parents that it would be good to mix [boys and girls] for sixth form as good preparation for university, but attitudes have changed,’ says Peterken.

‘There has been a shift away from the prestige brand. Parents are interested in the schools where their kids are going to be happy – they’re not so interested in it being Eton or Radley, as opposed to some other school.’

Dr Alex Peterken, headmaster at Charterhouse

Rather slowly as it happens. Dr Tim Hands, Warden of Winchester points out that their decision is not driven by financial need but rather has been on the cards for some time. Since 1985 to be precise, when a former warden James Sabben-Clare was actually appointed on the basis that he would bring in girls.

‘There is no shortage of applicants to the school as it is,’ says Hands who recognises that the demand for boarding and single schools boys schools is unlikely to be on an upward trajectory. Nevertheless, at Winchester, one of the most academic schools in the country, the move has been adopted because the ‘governing body have decided that now’s the time.’

So, the argument continues on when, how and whether to go co-ed. Much research has been conducted into the ‘best’ method of educating children, and those in both the single-sex and co-ed camp will always back their team. Successive pieces of research have found that girls do better in single-sex schools while boys do better in co-ed schools; in 2015, a study found that 75 per cent of pupils in all-girls secondary schools received five good GCSEs, compared with 55 per cent at co-ed schools.

A 2017 study by Utrecht University found that in schools with more than 60 per cent girls, boys had better reading scores: concluding that ‘boys seemed to be positively affected by a high proportion of female students in a school’. The study found that ‘girls possibly set a more successful learning climate in the schools and classrooms, to which boys were more susceptible’.

The school of thought that leads from this, that ‘girls civilise boys’ is, however, not a popular one. In a letter to The Sunday Times following Winchester’s announcement, Cheryl Giovannoni, Chief Executive of the Girls’ Day School Trust, suggested that ‘boys’ schools going co-ed do so to benefit boys. They are not aiming to give those girls the best possible girl-focused education, but for them to be a civilising influence on boys’. But, says Dr Stephen, ‘this is insulting to both boys and girls. The last reason on earth for bringing girls into a school is “to civilise boys”.’

Emma McKendrick, headmistress of Downe House School in Berkshire, concurs. ‘There can be a sense that girls are good for boys because they level things out, but that’s not a role I want our women to play, I want them to have an education in their own right’. Downe House girls leave school with ‘an expectation to be treated equally,’ says McKendrick.

Alastair Chirnside, the new Warden of St Edward’s School, Oxford sees Winchester’s decision as ‘a sign of the times’. Like Dr Peterken, he is an Old Etonian but believes that ‘co-education is a better way forward’. What crystallised this for him wasn’t his time working in single-sex education – most recently as Harrow deputy head – but choosing schools for his two daughters. ‘The biggest thing for me is the range of social experience that children have in their formative years. In a co-ed school, this is just wider,’ he says.

But what does that mean for the future of single-sex schools, if even an Old Etonian, former Harrow deputy head thinks co-ed is best? Leo Winkley, headmaster of Shrewsbury School, which went fully co-educational in 2014, believes, ‘it would be a real shame if there was no such thing as a boys’ school, and no such thing as a girls’ school, because that would have removed a really important choice.’

Dr Peterken suspects that over the next decade, boys’ school may become ‘even less appealing’. He has observed a shift ‘away from the prestige brand. Parents are interested in the schools where their kids are going to be happy – they’re not so interested in it going to Eton or Radley, as opposed to some other school’. Chirnside agrees. Parents, he says, ‘think more about school choice in the round than they used to, with more of an emphasis on wellbeing.’

That’s not to say that boys’ schools can’t, and don’t offer this. Sherborne School in Dorset is all boys, but neighbours Sherborne Girls, and the sixth form share some A-level subjects. ‘Where I think single-sex can go wrong is when boys don’t set eyes on girls apart from on Saturday nights’, explains Sherborne headmaster Dr Dominic Luckett. He avoids this by working closely with the girls’ school: ‘we have a big social programme, and do choir, orchestra, and drama together, as well as Amnesty International; many of our clubs are run jointly. Our boys work productively with the girls. If you don’t get those positive interactions, there is a danger that stereotypes can emerge of a single-sex-educated male who doesn’t know how to interact with girls’.

Dr Peterken admits this much: ‘Eton was wonderful but I felt pretty inept coming out the other end when I went to university’.

The latest scandal to rattle schools is the emergence of Everyone’s Invited, the ‘space created for survivors to share their stories’, with, at the time of writing, over 15,000 anonymous testimonies of rape culture recorded from pupils at schools of all shapes and sizes.

Jenny Stephen suspects that Everyone’s Invited will be even more of a reason for schools such as St Paul’s to take girls: ‘They’ll see it as a way of educating boys and girls to grow up together, and overcome some of these horrendous societal issues.’

Having more co-ed schools can only be positive for combatting the kinds of behaviour that have been reported, says Dr Peterken. ‘It can only help to have schools that are healthy with boys and girls living together and playing together, where mutual respect, kindness, and inclusivity is absolutely a part of the culture’.

It is not just independent schools that are in the spotlight for Everyone’s Invited, adds Peterken: ‘All schools have got to do better. We can’t solve this problem on our own, but as teachers and as leaders we’ve got a very important role in culture, in pastoral education, and in helping our young people understand issues around consent, relationships and pornography.’

‘It would be a real shame if there was no such thing as a boys’ school, and no such thing as a girls’ school, because that would have removed a really important choice.’

Leo Winkley, head of Shrewsbury School, London

Dr Luckett hopes that the relationship his boys have with Sherborne Girls helps to foster more positive experiences. ‘No school with boys in it is immune from these issues, but a few years ago we set up the Joint Pupil Pastoral Forum, where boys and girls can talk about a range of pastoral issues. We’re very lucky in that respect – I’m not sure what outlet there is for that in a standalone boys’ school with no access to an equivalent girls’ school.’

Interestingly, when the tables are turned, it seems that the girls’ schools have no interest in bringing in boys. Their resilience is testimony to the success of the all girl’s model or is it something more? When I ask Samantha Price, headmistress of Benenden in Kent whether she would take boys, she laughs, and says, ‘I don’t think the alumni would allow it. What I would like to do is open a Benenden boys, but I haven’t got the money’. Price believes that far from the single-sex sector declining, it might even be on the up: ‘numbers here continue to be very strong’. But that, she says, is about the quality of the school, more than the structure. ‘We get a lot of parents who look at us alongside co-ed schools because they’re not sure. It might be that single-sex is a driver, but it’s what we offer that they think is right’.

It is the job of all heads to sell you their dream, but at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter where you send your child as long as they’re happy. ‘I started my career in a boys’ school’, says Price, this year’s President of the Girls’ Schools Association. ‘I don’t think there is one type of school which is better than another’. And who knows what’s around the corner? The day before Winchester College announced that they would be taking girls, few could have suspected it. Is Eton next? As Dr Peterken puts it: ‘Eton might be over 500 years old, but it will want to have an education which is future-ready. I hope they would keep open-minded about it, but let’s not underestimate the challenges of going co-ed. It’s not as simple as flicking a switch.’

READ MORE FROM AUTUMN/WINTER 2021

Focus: Safeguarding our Future | Best of… Intrepid Explorers