British Crafts Industries: Emma Crichton-Miller On The Human Touch

Read Emma Crichton-Miller's essay on the human touch from this year's Great British Brands

This post may contain affiliate links. Learn more

Craft has reclaimed its rightful position as the true ingredient of luxury, says Emma Crichton-Miller. Essay taken from this year’s Great British Brands.

Check out our Great British Brands here

A Change From London Fashion Week…

Holders of a hot ticket to Christopher Bailey’s 2016 London Fashion Week show, were greeted with a surprise. The then creative director and CEO of Burberry, who recently announced his departure, launched the S/S’17 collection in a pop-up space, a disused Soho warehouse, renamed Makers House, its courtyard enticingly decked out with plants and statuary. On the top floor fashionistas could admire the brand’s first straight-to-consumer collection in its entirety. But to get there you had first to navigate a multi-room installation dedicated to craft, curated by upscale craft shop, The New Craftsmen.

There were live demonstrations of silver casting and traditional Japanese lacquer techniques; one artist demonstrated silk-screen printing for scarves; another embroidered visitors’ handwriting onto cloth, while a pop-up concession of Thomas’s café served tea in slipware made by Devon craftsman Douglas Fitch and Scottish potter Hannah McAndrew. Aimee Betts and Harriet Stiles made a one-off hand-embroidered velvet bolster cushion, Marlène Huissoud decorated vessels made from bee resin while artists from the Royal School of Needlework hand-stitched insects to linen cushions using the Elizabethan technique of blackwork embroidery. Everywhere there were examples of the exquisitely made and scarily priced home goods to be found in the Mayfair shop.

The Connection Between Craft and Luxury…

The statement could not have been louder that craft and craftsmanship are core values, intrinsic to the Burberry brand. Christopher Bailey’s father was a carpenter and Bailey has long been a vocal champion of people who make things by hand. This display was not just an exuberant personal indulgence but a carefully choreographed piece of marketing, celebrating a marriage between superior craftsmanship and high-end commerce. Far from being a singular flight of fancy, it is emblematic of a larger movement, common throughout the luxury business, to reposition luxury as the guardian and champion of craftsmanship, rather than as craft’s glamorous and triumphant rival. Partly this makes economic good sense. As the once-lucrative market in Asia, where brand names still have cachet, has slowed down, it makes sense to court the cosmopolitan London audience, for whom The New Craftsmen’s refined wares are a badge of sophistication. Of course it also confirms how definitively craft has been swept up and adopted by the luxury market as a guarantee of authenticity, quality and rarity. Now that brand names are everywhere, how else to justify the enormous price tag on those Gucci shoes or Prada bag than to explain that highly skilled hands devoted hours to their creation? There are echoes here of the Hermès travelling pop-up show, launched in 2011 and titled Festival des Métiers, which showcased artisans demonstrating how they make the famous brand’s bags, saddles, silk squares, ties, watches and gloves, and which arrived in Paris last November. Or think of Louis Vuitton’s December 2015 exhibition at the Grand Palais, called Volez, Voguez, Voyagez – Louis, now travelling the world, which included displays of the many crafts employed across its products.

Other high-end names flaunting their craft credentials include Alexander McQueen, under creative director Sarah Burton, who took her team to Scotland’s Shetland Isles to inspire their spring 2017 collection. They later fielded an array of fine-spun knits, narrative embroideries and heraldic leatherwork. The Northamptonshire shoe manufacturers Edward Green, Church’s, Crockett and Jones, Joseph Cheaney & Sons, John Lobb and Tricker’s, among others, parade their ancient bearded ancestors on their websites and vaunt the traditional skills of their craftsmen. Alongside the value of handwork is the allure of story – the rich background narrative which gives depth and meaning to the product. At its most perfunctory, all this rhetoric of heritage and craftsmanship has become so ubiquitous that we no longer hear it. We deride the hand-crafted sandwiches and heritage tomatoes we are offered. But it is in truth a remarkable reversal in values. One-hundred and fifty years ago luxury and fine craftsmanship were indivisible. When, in 1837, Thierry Hermès first established a harness workshop on the Grands Boulevards of Paris, providing incomparable saddles and bridles to European noblemen, the only mark of excellence was craftsmanship: the quality of the chosen materials, the quality of the design and the quality of the workmanship. Similarly, the great jewellery and watch marques won their reputations by combining the finest materials with ingenious design and meticulous handwork.

This intimate connection between craft and luxury was slowly eroded throughout the 20th century. First modernism offered a different set of values to those which had sustained the luxury market, championing mechanisation and a simplified aesthetic. Then, after the Second World War a democratic spirit relegated luxury to the past: the future was to be bright, plastic and mass manufactured.

A Manufactured Future…

At this point, as Guy Salter, Chairman of London Craft Week, puts it, the western world experienced the roller coaster of ‘the discernment curve. Consumers joined the luxury market without having enjoyed the experience of fine craftsmanship. Small family businesses grew into large businesses catering to a much bigger market, requiring them to abandon their small-scale, hand-crafted processes.’ Luxury became a matter of marketing, a signalling of prestige, rather than a quality that could be appreciated. ‘There was a huge dip,’ Salter says, ‘in the level of discernment.’ In the 1970s and 1980s, the craft world also seemed often at odds with mainstream society. While there were fine potters and glass makers or goldsmiths and textile artists creating beautiful work, craft more generally was a niche interest with little impact on contemporary design or fashion, which were more interested in exploring new materials and new technologies to reach new consumers.

Keith Levett, a master tailor and director of Savile Row company Henry Poole & Co, who specialises himself in the meticulous hand-making of bespoke ceremonial and livery costumes, remembers those days well. ‘By the late 1980s/early 1990s, apprenticeship was a dirty word. There were comparatively few people coming into the trade. Companies were not thinking about the future.’ He remembers reading a series of articles in Country Life in the 1990s about Living Treasures of Craft, ‘a glorious survey of incredibly talented people’, he says, but written ‘as if these crafts were on their last legs’. Then there was the recession of the 1990s, when luxury brands, in the words of Salter, spent ‘all their money on rent and marketing, and very little on craftsmanship and quality’.

Giorgio Riello, historian and co-author of the recent book Luxury: A Rich History, comments, ‘At this point craft wasseen as being very western and based on an idea of heritage. It became part of a package, along with imagery from the 18th and 19th centuries – very Downton Abbey – to sell commodities.’ Big brands would make flamboyant but cynical claims about tradition and artisanal practice when in fact all it meant was a little hand-finishing to products mass produced through advanced methods of production. Anything that would tempt consumers to pay over the odds.

The Tide Has Turned…

Over the last ten or 12 years, however, the tide has turned. Organisations such as QEST, the Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust, set up in 1990 by the Royal Warrant Holders Association to offer scholarships to talented craftsmen and women, and the Crafts Council, have worked hard to support crafts skills, and boost their profile. Through exhibitions, fairs such as Collect that it is simply Cinderella being dragged out for show – so it has also staged its own challenges.

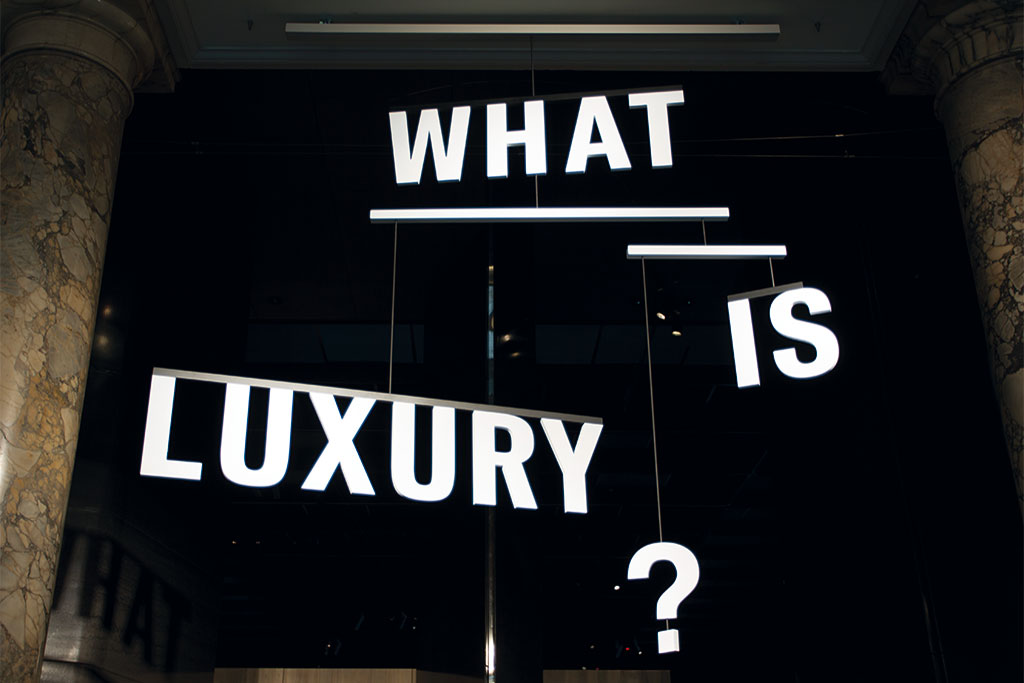

In 2015 the Crafts Council and the Victoria and Albert Museum mounted the provocative exhibition What Is Luxury? Instead of a series of branded handbags, visitors experienced combs constructed from human hair by Studio Swine, the exquisite Golden Fleece Headpiece of master goldsmith Giovanni Corvaja, intricately woven from 160 kilometres of superfine gold threads over 2,500 hours and some remarkably beautiful plastic tables created by Chinese designer Gangjian Cui through a hand-operated extrusion machine. The show asked: Is luxury about materials? Is it about time? Is it about rarity of resources? Is it about skills?

Annie Warburton, Creative Director of the Crafts Council, reminds me too that there is a luxury in having the time and resources to perfect a skill: it is this luxury you are also buying when you acquire a beautifully hand-crafted object. She is hopeful that luxury brands have moved away from their flashy image to promote ‘something much more subtle, to do with connoisseurship’. She also sees in the public an eagerness to ‘have objects with a story behind them’ – not one spun from the candyfloss of cliché and nostalgia but stories of real makers and real places.

In turn, the luxury brands have responded. Mulberry has invested heavily in the training of leather workers, Linley supports talented cabinet makers and the Savile Row Bespoke Association, founded in 2004, requires its members to take on at least one full-time apprentice. In 1997, Savoir beds took over the bespoke, hand-made bed-making business of The Savoy Bedworks, saving skills that had been passed down without break from 1905, while in 1970 Halcyon Days rescued the 18th-century art of enamelling on copper from extinction, building a business in hand-painted enamelled boxes and bangles which thrives to this day. Meanwhile William Asprey, scion of the venerable Bond Street store, Asprey, set up his own luxury brand, William & Son in 1999 and, in 2010, sealed his commitment to British craftsmanship by buying up and expanding three British factories that produce leather, tweed and cashmere.

Finally LVMH-owned Spanish brand Loewe, under creative director Jonathan Anderson has taken luxury’s love-affair with craft a step further, by becoming a patron. A connoisseur and collector of British craft, who has displayed studio ceramics in his stores, Anderson was behind the launch of the Loewe Foundation’s Loewe Craft Prize in 2016, stating ‘Craft is the essence of Loewe. As a house, we are about craft in the purest sense of the word. That is where our modernity lies, and it will always be relevant.’ The inaugural 2017 winner of the €50,000 prize was the magnificent German wood artist Ernst Gamperl. As with Burberry’s ongoing collaboration with The New Craftsmen, it seems luxury has at last embraced craft as an equal twin: to be nurtured, celebrated and sprinkled with the dust of glamour.

For the sake of both, let us hope it is not just a gesture.

MORE ESSAYS: Is High Culture A Luxury Or A Necessity? | How to Invest in Jewellery / The Evolution of Great Brands / Everything you need to know about hygge