A Thoroughly Modern Miss Dior: A History Of Fashion’s Biggest Brand

By

9 months ago

Maria Grazia Chiuri’s AW24 Collection traces its roots back to Marc Bohan’s 1960s tenure at Dior

As a Dior pop-up comes to Harrods this summer, Lisa Armstrong traces Maria Grazia Chiuri’s AW24 collection to the transformational late 1960s when fashion left the atelier to conquer the world.

The Rise Of Miss Dior

On a chilly day last February in Paris, Maria Grazia Chiuri, creative director of Dior’s womenswear, presented a packed autumn/winter 2024 collection in front of a huge audience of top journalists, key clients and celebrities (Jennifer Lawrence, Elizabeth Debicki and Natalie Portman). Models weaved their way through striking artworks by a woman artist with something to say about the female state (in this instance, Indian sculptor Shakuntala Kulkarni’s cane, armour-like structures).

In many ways, for Maria Grazia it was business as usual – superficially at least. However, the clothes themselves were very different from Chiuri’s normal playbook, which riffs ingeniously each season on the iconic bar jacket and its pleated, calf length silk and tulle skirts. In the seven years she has been at the house, Chiuri has turned these flattering period pieces into featherweight, airy go-tos for today’s customers, making them far lighter and more user-friendly, while retaining that distinctive, waist-defining silhouette.

But not this time. For autumn/winter 2024, Chiuri parked her wagons in the 1960s section of the Dior archives. More specifically, 1967, when Dior launched Miss Dior, its first ready-to-wear collection – a momentous moment in fashion when the grandest of Parisian houses acknowledged the winds of social change.

For her 2024 take, Chiuri leaned gleefully into the snappy separates of that first Miss Dior collection, monetarily departing from the wasp waist and fairytale lace ball dresses that are her normal anchors. In their place came a modern, almost sporty aesthetic featuring sharp, knee-length trench coats, gently A-line, just-above-the-knee skirts, pea coats and boxy jackets. For evenings, she presented a series of impeccable, long, sheath dresses that flowed gracefully from the shoulder line. For fun, there were accessories and clothes spattered with a hand-painted graffiti’d version of the Miss Dior logo, originally templated by Alexandre Sache for the scarves in 1970 (so different from Christian Dior’s distinctive original neat front). For 2024, it has been blown up large and now has an almost punk energy.

Aside from the fact that M Dior didn’t like the look of knees (‘the ugliest part of a woman’s body,’ he once opined in a declaration that probably wouldn’t get past any switched-on press team today), he would have approved. This contained everything many women today would want in their wardrobes, down to the low block heel, square-toed shoes and swingy, neat handbags – just as it had in 1967. Almost from the moment he launched his house 20 years earlier in 1947, Christian Dior harboured ambitions to make Dior the ultimate shopping experience. ‘I wanted a woman to be able to leave the boutique dressed by it from head to toe, even carry a present in her hand,’ he later reflected.

He was as good as his word, adding perfumes, stockings and furs (different times). For all his charm, diffidence and reputation as a dreamy rose sniffer, M Dior was a formidable and farsighted businessman. At one point the house of Dior franchised more than 150 lines. But it didn’t produce ready-to-wear. At least not for another 20 years after that momentous postwar debut. That would be a much harder battle.

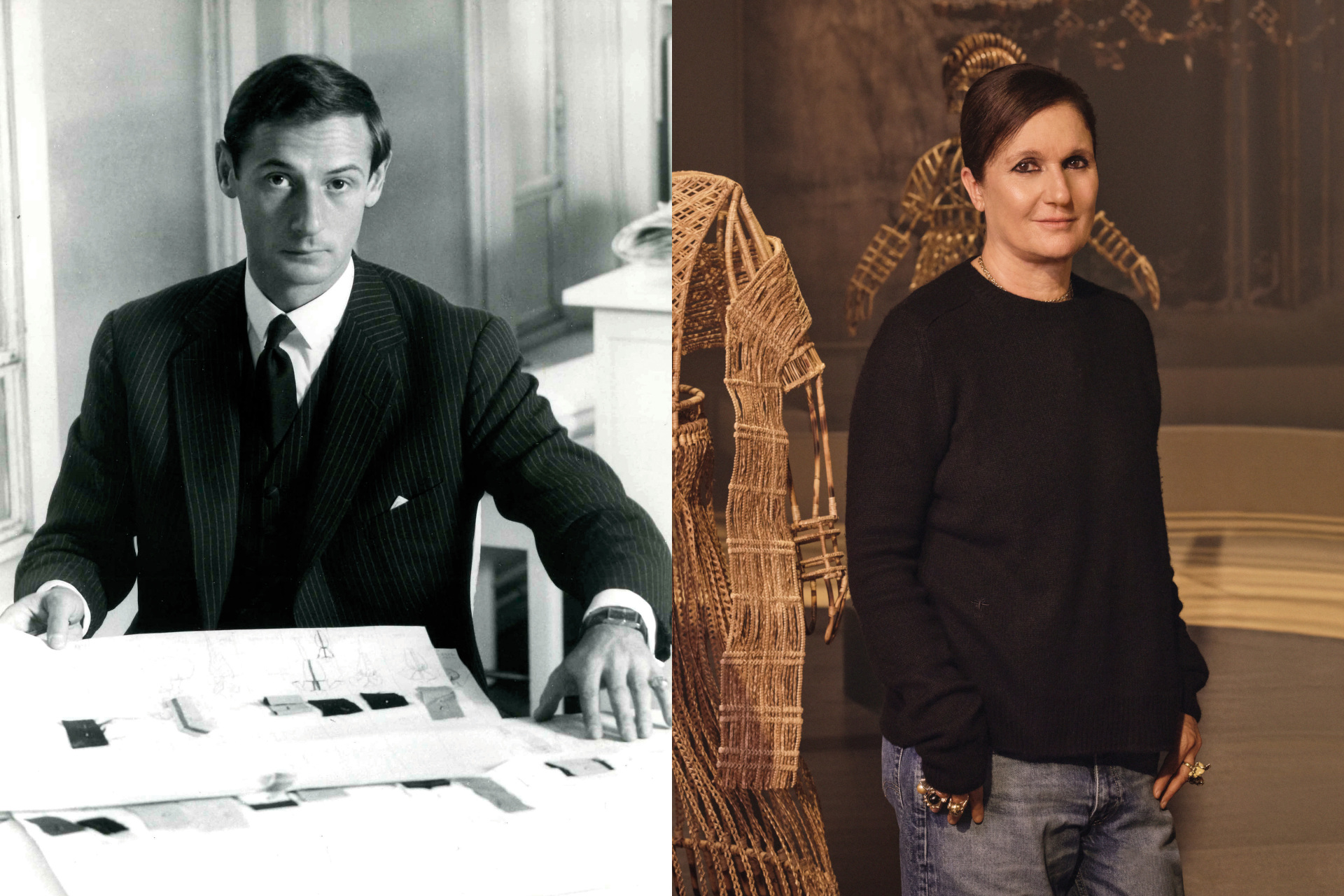

Dior’s former creative director Marc Bohan and current one Maria Grazia Chiuri (left image by Georges Saad)

In the late 1940s, the fashion system was structured so that couturiers could design made-to-measure and bespoke clothes for an elite cadre of very wealthy clients – but not much else. This was the very definition of slow fashion. After each couture show (there were just two a year), customers would deliberate over their selection, then make the pilgrimage to Paris for two or three fittings, and wait up to three months for their orders to be completed.

Those who were wealthy, but not stupendously so, could buy licensed copies of the twice-yearly couture collections from prestigious department stores in their nearest city – if they happened to live within striking distance of London, New York, Rome or Buenos Aires… These were adaptations, more catered towards the ‘real-ish’ end of affluent life. Still pricey and prestigious, but not as expensive as couture from the fountainhead.

Bergdorf Goodman and Saks Fifth Avenue in New York; Harrods and Selfridges in London, along with scores of other official partners around the world, paid designers for the rights to copy an agreed number of their designs. These were produced by the stores’ manufacturers, to an agreed standard in high-quality fabrics. In practice, sometimes the results varied. In 1952, in an attempt to elevate the processes and bring it under his control, Christian Dior opened his own work rooms in London and launched CD London. The clothes took their cue from the collections he showed in Paris, but were slightly modified for a British customer. There was a launch catwalk show at the Savoy – it was still highly elitist

In 1967, Marc Bohan, the second designer to take the reins at Dior after the great founder’s death in 1967, attempted to redress that by introducing Miss Dior, a ready-to-wear collection aimed at a younger (although still well-off) customer with a (slightly) more rebellious sensibility who, even had she been able to afford couture, didn’t want to sit around waiting three months for it to arrive. Still luxurious, with elevated fabrics, Miss Dior was designed, under Bohan’s watchful eye, by Philippe Guibourgé, a successful ‘ghost’ designer of the era, working anonymously.

Dior AW24 (c) Adrien Dirand

Guibourge would later launch a ready-to-wear collection at Chanel in the 1970s, to moderate interest, only leaving the house when a certain German called Karl Lagerfeld was hired to rev things up. The Miss Dior collection of 1967 seemed more modern than anything he did at Chanel. It was expressly conceived to be practical, easy and, crucially, reflective of the way young women were dressing at that time.

And what a time. In 1967, rebellion if not revolution was in the air. The Civil Rights Movement was in full swing in the US, together with marches, protests and sit-ins that only grew in intensity as students joined to protest against the US’s war in Vietnam and the draft. A new guard was emerging with a very different world view from that of the immediate postwar generation. Their outrage against social and racial injustice spread across Europe. Demonstrations and strikes against capitalism, consumerism, the police and American imperialism sprouted like mushroom fields. By May 1968, the situation in France became so precarious, President de Gaulle secretly fled the country for Germany. The French economy ground to a halt. It was either an insane idea to launch a new fashion line or a genius one.

It says much about Bohan, Dior’s then creative director, that he went ahead. To do otherwise would have made a house that was born out of Christian Dior’s urge to change everything that had been fashionable in 1947, seem stultified. Yves Saint Laurent had already introduced his own ready-to-wear collection in 1967, declaring that ‘couture is dead’ (although he carried on designing and selling couture until 2002 when he decided to close his house and retire).

Bohan, far less of a showboater than Saint Laurent, declined to make contentious statements in public, preferring to stress his commitment to the customer. ‘My style remained constant over my career. I wasn’t designing for anybody except for the women who were my clients,’ he said. He was the ultimate discreet designer, dedicated to offering a perfected, understated elegance to a few thousand rich clients, including Sophia Loren, Lauren Bacall, Bianca Jagger and, perhaps most famously, Princess Grace of Monaco who remained a loyal customer for the 28 years Bohan was in charge. Her eldest daughter, Princess Caroline, wore Marc Bohan for Dior when she married her first husband in 1978. Elizabeth Taylor ordered 12 dresses from his 1961 collection and considered a Bohan dress one other lucky charms because she’d worn it to collect her Oscar for Butterfield 8 in 1961, her first, although she’d been nominated four times previously.

Bohan could see the way the world was going in 1967 – and momentarily at least, it was charging headlong towards a heady nirvana of egalitarianism.

In many ways, of the six men who preceded her at the creative peak of Dior, Bohan is the one Chiuri most identifies with. ‘He’s so often underestimated,’ she said backstage in Paris before Dior’s autumn/winter 2024 ready-to-wear. Ease and movement were two hallmarks of Bohan’s work. ‘Elegance is simplicity in refinement,’ he once said.

‘In a sense it [his work] was feminist, long before women had begun burning bras,’ said Chiuri, before unveiling her own take on the 1967 Miss Dior collection back in February.

Chiuri always grants a handful of journalists from each major market generous backstage access before all her shows. It’s an effective way for her to communicate the research, intellectual rigour and craft that goes into clothes that often wear their credentials lightly. Like Christian Dior himself, she aims to give a modern woman a complete wardrobe. For her, that means the perfect denim as well the dreamiest red-carpet looks. And like Bohan, she doesn’t care for extreme sartorial statements that can make the wearers look self-conscious, awkward or ridiculous.

‘Bohan wasn’t interested in personal fame. He just wanted to give women a wardrobe of beautiful, sleek clothes. That’s not easy – and it’s not all he did. In his own way, he was very innovative,’ says Chiuri, who has made it her business to study his vast contribution to the house. Bohan’s so-called slim look, which drew inspiration from Britain’s Mod culture and which would influence the 1967 Miss Dior debut, was a case in point.

Tellingly, Bohan was the first choice to replace Christian Dior in 1957 of Marc Broussac, the cotton-empire magnate whose money had set up the house. Boussac, while recognising the prodigious talent of Saint Laurent, who had taken over the reins when Christian Dior died suddenly in 1957, fretted that he was too fragile to run a house, and was wary of his designs, considering them too radical, too biased towards the young to be sufficiently tempting for couture buyers. It was Boussac who hired Bohan as an insurance precaution, to run the studios under Saint Laurent in 1958. Bohan had already worked in Paris for 13 years, the last four as designer at Jean Patou, and understood clothes also had to please paying customers who were not models. Originally, Bohan was engaged on a two-year contract, during which he was dispatched across the Channel to head up Christian Dior in London. When Saint Laurent was conscripted to the army in 1960, he had a nervous breakdown and never returned to Dior, and Bohan was anointed his successor.

Bohan’s and Chiuri’s interpretations of feminism have plenty in common. Yet in 2019, Chiuri told me she was a late adopter of overt feminism. She grew up, as so many of her generation did, assuming feminism was a done deal. ‘I thought we’d won,’ she says. ‘Living in Rome, particularly, there was evidence all around that this wasn’t the case. But the countless small (and larger) ways in which women were held back were so ingrained into the texture of society, you almost stopped noticing them as anything.’

Although Chiuri was busy living the life of a feminist – steering a stellar career, and raising a family that remains close even now when it’s scattered across three countries, with a husband, Paolo Regini, who has his own successful tailoring business in Rome – she just didn’t get round to talking about being one. ‘I mean, OK, in the 1980s you weren’t really supposed to be a feminist and like fashion. But that wasn’t my experience. I went to Fendi and it was run by five women.’

Then came the big one – her appointment to Dior in 2017. She read everything there was to read on this most archly feminine of fashion houses and concluded: ‘The risk of femininity is that it can seem dated. And that it’s filtered through man’s view of femininity.’

You only have to look at Chiuri’s playful update of that first Miss Dior collection, with its easy-to-wear, super-sleek skirts and matching trench coats, mid-heel tall boots, zip-up, mini cashmere and quilted nylon anoraks, scoop-fronted knitted tanks, worn over unbuttoned shirts (sexy and cosy), distressed denim suits and dinky shoulder bags, some in neon, to see her feminine/feminist filter at work. It’s a line of emancipated beauty that can be traced directly back to Bohan, while feeling completely right for now. It’s armour in its way: you feel ready for anything in these clothes and slightly more athletic that you might in other tailored clothes. But it’s a million light years of emancipation away from the Shakuntala Kulkarni works that were juxtaposed on the catwalk with the collection for that February show in Paris.

Chiuri’s cleverness lies in encapsulating that sense of momentous fashion history into something you want to wear today. Whether you’re a big spender or a student of fashion, it’s worth visiting Harrod’s Miss Dior takeover, which includes exclusive products from the collection such as neon-orange and lime shoulder bags, and book bags specially designed for the store. Stand back and let that intoxicating rush you get when history and modernity click together perfectly wash over you.

Visit The Pop-Up

The Miss Dior pop-up will be at Harrods from 31 July to 25 August 2024. harrods.com

Images courtesy of Dior