How Kate Middleton’s Favourite Trainers Are Saving The Soil

By

10 months ago

Veja is winning the regeneration race

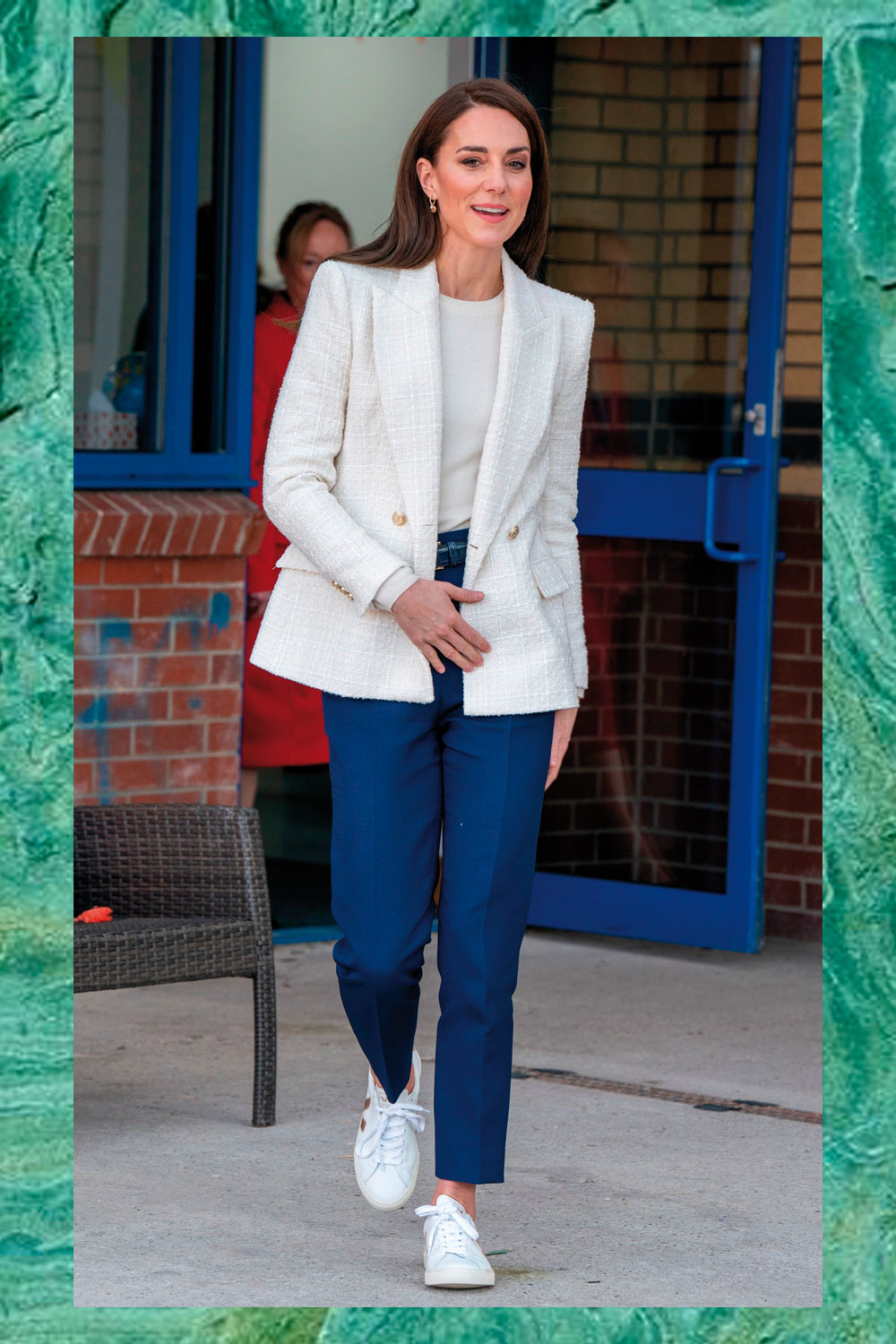

Veja, the sneaker brand favoured by Kate Middleton, are beloved by its Brazilian farmers. How did it win over both parties? Perhaps through the brand’s ethical and conscious business practices, suggests Tiffanie Darke.

How Veja Developed A Better Business Model – A Regenerative One

At first glance there may not be much the Princess of Wales and the Brazilian farmer Valquíria Viana dos Santos have in common, but both like the same sneakers. For Kate, they are an inevitable part of her mum-on-the-run uniform; for Valquíria, they are a cash crop allowing her to remain on the land her ancestors were brought to as slaves.

The sneakers are made from cotton canvas and Amazonian rubber, and are made by Veja, a French company that is becoming a best-in-class model for regenerative business.

While we in the West might struggle with what this actually means, Valquíria feels it every day. It has been the key to expanding her family agro-ecology business and generating an income that allows her to raise her sons as a single mother. Veja pay Valquíria three times the market price for cotton, which she sells direct to them through her local co-operative. She also qualifies for a bonus if she stewards her farm correctly. Veja requires an organic practice, multi-cropping, and a careful written record of weather, harvests and soil health. Which is more or less how these family farmsteads have farmed for generations.

Valquíria, who runs a baking business on the side, is one of thousands of small-scale agroecological farmers who hold the secret to the future of farming and supply. This fact may be lost on her as she stands resplendent, in flawless makeup, in the heat of the morning sun, but she already has plans to take on more land. ‘My dream is to have my cotton crop bigger – to have commerce for all our people,’ she says, surveying her rows of cotton, corn, sweet potato and pepper. ‘Then life conditions would improve greatly.’

Valquíria, right

Sadly, Brazil’s wider cotton industry is not in such good health. According to the NGO Earthsight, there are proven links to deforestation and human rights abuses. Even crops trademarked ‘Better Cotton’, a certification brands such as Zara and H&M rely on, are open to abuse. Earthsight’s revelations precipitated stinging letters from these high-street brands: Better Cotton is the only transparency they have on their complex and varied supply chains. With Better Cotton’s reputation in tatters, so is theirs.

Sebastien Kopp and François-Ghislain Morillion, the friends who co-founded Veja in 2004, have set up their business to ensure they will never be in this position. Their intention was this from the get-go: to know exactly where everything came from and to build a best-in-class supply chain, investing in every pair of hands and field that touches their product. Looking for a way out of banking (‘it was boring’), they went in search of a better way to enjoy life. Money, they agreed, wasn’t the end – it was the means. They toured the world looking for inspiration, concluding that a Brazilian Fairtrade coffee model seemed the closest to ‘good business’ – giving small farmers a direct and well-paid route to market. And for them, an excuse to spend time in a country they love. They swapped coffee for cotton and rubber, and as they were both obsessed with sneakers, designed a shoe. They called the brand Veja because it means ‘look’ in Portuguese, and that’s what they were doing, looking all the way back to the beginning of things. Their growth has been experimental, cautious and steady, but they have just opened a shop in Covent Garden, following ones in Paris, Tokyo and New York. Without making any compromises along the way, they have grown to sell four million pairs of shoes a year.

‘The fun of it also grows,’ says François. ‘The business is like a living thing, like a tree that grows a new branch every year, not going too high and sometimes losing a bit of self too. Seventeen years is nothing – it takes two to three hundred years in a forestry cycle to get the really big trees.’

A model wears Veja trainers

It is François who brought me to Valquíria’s house. The easy way he chats with her mother, cuddles her cat and jokes about his love of cakes makes you understand how this supply-chain relationship works. He and his on-the-ground team visit these farmers all the time. They know them personally, their families, their fields, as they do the rubber farmers in the Amazon and the rubbish collectors in Rio who source the plastic bottles they recycle into PET for the eyelets in the shoe. François is big with the hugs, quick with the jokes, adores everyone he meets and listens – really listens – when they talk. ‘We can learn so much from them,’ he remarks following an involved conversation about the biduca pest, the blight of the cotton plant. Veja makes a ten to 15 percent profit margin on each shoe because everything goes back into its supply chain. Would Veja ever be tempted to plough its profit into sports stars and ad campaigns, like other trainer brands? ‘Where would be the fun in that?’ he replies.

Veja has become the primary supporter of thousands of small, family cotton farmers in the north of Brazil, offering them the opportunity to stay on their land, to grow a safe path forward. As Valquíria says, ‘Few women want to work in the field, as it’s hard. But if you focus, you get the reward. Everything we want in life requires determination to make it happen.’

So how should we, the shoppers, make decisions about what we buy that can help enable supply chains such as this one, as opposed to ones chopping down the rainforest and exploiting workers? When we cannot rely on certifications such as the egregiously misrepresentative ‘Better Cotton’, it leaves us out on our own.

If you want brands you can really trust, you have to look. Look at where something has come from, how it is made, what happens after it is sold, (mending and recycling services), and what benefit society is gaining from it (Veja’s logistics operations are staffed by disabled and marginalised people). That’s when you find the purest form of good business. In my view, it begins with intention. What are you trying to do here? Make a cool product, make lots of money, or improve the world? If you start with the last, the other two might just follow.