The Past, Present and Future of British Fashion

Vogue Runways' Sarah Mower discusses the role of British fashion in the luxury market

This post may contain affiliate links. Learn more

As a Brit working for an American company, Sarah Mower has a unique viewpoint on the British fashion industry – she’s thrilled by what she sees, but says we ought to stop being so damn self-deprecating.

In Come The Brits

The British have entered a philosophical state of wondering what we mean to the world. The 48 per cent of the population who voted to stay within Europe harbours fears that we may lose our attraction as a vibrant, internationally integrated modern culture. The 52 per cent who voted to leave the European Union, including many in the Conservative government, believe that the ‘rest of the world’ outside Europe is just raring to buy into our stalwart British qualities when we go it alone. Beyond the hopes and the fears, and all our wildly divergent views about our national identity lies a complex and surprising merge of realities, however. As someone who’s English, but works for an American company, I can see things simultaneously as an insider and an outsider looking in. Fashion – I report on it as an observer – provides a window through which we can get quite a good look at what the world actually does think of us, and what exactly other nations are particularly drawn to buy from us.

The Landscape of Luxury

Let’s get this perspective off on the right foot. How can fashion be relevant to a country’s prospects? It’s fair to say that hardly any of the British population – leavers or remainers – has the slightest inkling that fashion and fashion exports are worth £32bn; a figure that outranks the UK’s automotive, telecommunications and pharmaceutical industries. The status of what we produce in the way of innovation on the one hand, and compelling classics on the other, is something the British don’t see – we are that self-deprecating – but which others really enjoy. Yet the latest figures – you can take London Fashion Week as symbolic – prove how international interest has been climbing; unaffected by the all-consuming national bout of navel-gazing going in British politics.

Despite everything, the shows for spring 2019 attracted a 38 per cent increase in international press attendance, and a 30 per cent upswing in buyers from China, the USA, Japan and Korea. The week was packed with the myriad talents London showcases – itself a snapshot of the international creative crucible it’s become. Someone like Mary Katrantzou, who has grown up as part of the London designer boom of the last decade is emblematic: she is Greek, studied at Central Saint Martins (the world’s Harvard of fashion education), has a Chinese investor, Wendy Yu, and dedicated, high-spending clients from Texas to the Middle East. Many of them turned out in Mary’s sparkling, embroidered gowns for her tenth-anniversary show. Mary started her business straight out of university in 2009 just as Lehmann Brothers was crashing. Her success – started on the strength of ten dresses characterised by her brilliant digital prints – proved how well the British training in bold innovation can make new products stand out, even against the starkest financial backdrop. Buyers jumped at Mary’s colourful, accessible dresses at a time when other designers had turned bland and cautious. Yet Mary Katrantzou’s success also challenges fixed nationalistic assumptions about what constitutes a ‘British brand’ today. It’s a phenomenon visible far and wide, and in multiple permutations, right across the British landscape of luxury.

The Mega-Fashion-Show

One of the reasons press and buyers flooded into London in September was to see the much anticipated mega-show debut of the designer Riccardo Tisci at Burberry. The venue was vast; held in an ex-post office sorting office, next door to the new US Embassy building in an area of Battersea which is now a citadel of newly built luxury apartment towers (largely bought by the Russian, Chinese and Middle Eastern super-wealthy who like owning square metres in London). Probably there’s no object to which the world ascribes more quintessential Britishness than a Burberry trenchcoat. A brand empire has been built on it. Nevertheless, Burberry is in fact as internationally based as were the show’s surroundings. Riccardo Tisci and Marco Gobbetti, the CEO who hired him, are Italian; the in-house teams are talents of many nations, and Burberry itself is a publically traded company. Creatively, Tisci said that his viewpoint is determined to be thoroughly inclusive. He envisions a brand which is inter-generational as well as internationally appealing, across the world. ‘I want it to be for the mother and the daughter, the father and the son,’ he said.

Tisci’s bond with London is that he was educated at Central Saint Martins, too. Yet the most signal novelty on his catwalk wasn’t his reference to punk and street-style, it was his embracing of classics for adults. Suits and camel coats for business people; wardrobes for men and women who want their clothes to be appropriate for their smart lifestyles. Something well-cut, contemporary, not wildly ‘fashion’. And strangely enough, the calm and the considered now reads as progressive; almost avant-garde.

Emerging Talent

This leads us to another sector in which a certain type of traditional British brand can quietly triumph. There’s a place – and a growing one – for wild young British designer fashion, especially in menswear. But equally, as people become more and more informed, so the value of the ‘classic’ is being reinvested with an aura of desirability. Increasingly, people want to know who made their clothes – and not only those with esoteric traditionalist tastes. In an era when realisation about the environmental and human impacts of the over-production of clothes is coming home to roost, the status of an interest in ‘craft’ has been transformed from fusty to fashionable. For as long as I can remember, it is Japanese buyers who’ve set the bar high for this kind of consciousness; Japan has led appreciation for those British companies which use traditional processes, from fibre to garment– and which have a real personality behind them. No wonder tweed and clothes made for traditional British country pursuits have become so fashionable in the past year. No doubt the emergence of a new generation of young British royals has helped modernise it too.

There are moral, human values as well as a tint of romantic escapism placed on patronising British weavers, knitters, hat-makers and shoe-makers. The more characterful, specialised and particular the brand, the better. In the age of the internet, the connection between clothes and their provenance can be accessed within a click or two. I am thinking of the appeal of a brand like Holland & Holland, traditional gunmakers established in 1832. They’re still gun specialists, but they now have an outdoor, everyday clothing collection for women and men. Its designers are two aristocratic, elegant friends who live in Scotland, Stella Tennant and Isabella Cawdor, who not only appear in Holland & Holland’s campaigns (sometimes with their tribe of children), but are excited to talk about the cashmere industry in Hawick and the individual weavers they work with on the Isle of Harris. The resulting Holland & Holland imagery – photoshoots, videos, documentary material – on their website and Instagram creates an aura around the brand which has both a high-fashion appeal and down-to-earth realness. What’s fascinating, though, is that Holland & Holland is owned by Chanel. That this most discreet of French luxury companies sees the business advantage in owning and upholding this tradition of provenance, British personality and authentic knowledge of a certain way of life speaks volumes for its validity as an internationally selling brand. It’s just one brand in a myriad culture of small British country-life businesses in the same vein, whose chances to show the world what’s special about them have been transformed by digital communications.

Supporting the Skilled

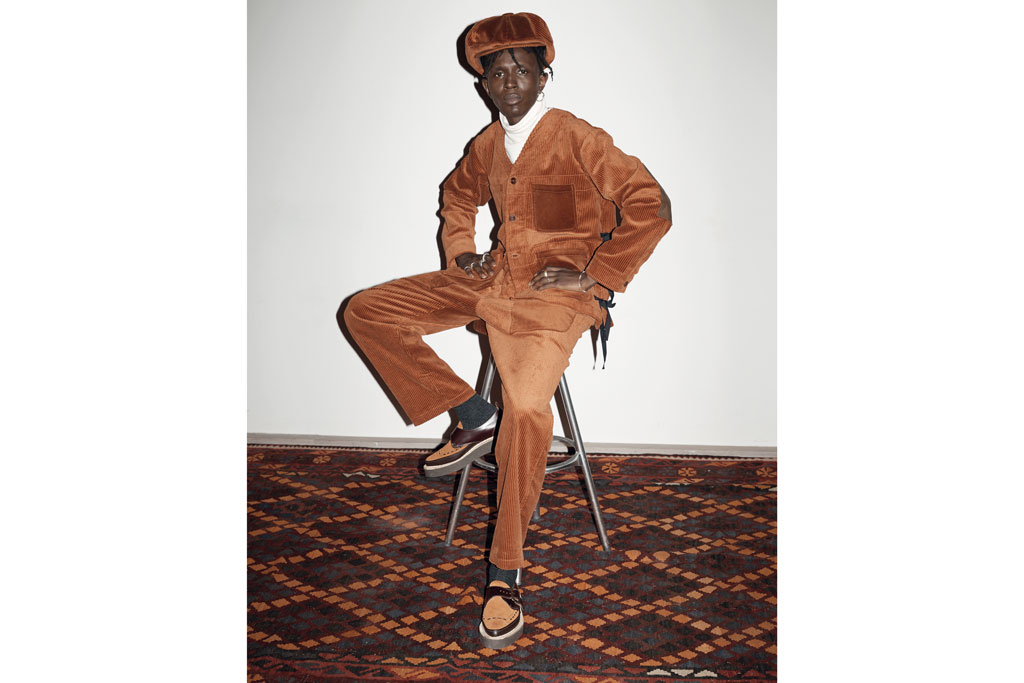

The truth of the matter is that most British fashion brands who make luxury or designer clothes and accessories are small and medium-sized (Burberry and Mulberry being a couple of exceptions). Yet as the world is turning, that’s a potential attraction, too. As the over-saturation of mega-brands breeds consumer ennui, the pleasure and one-upmanship in discovering and owning well-designed things which only the few know about, ahead of everyone else, is growing. To watch now are the micro-indy names of the London community who are melding tradition, sustainability and cool. Take Le Kilt, by young Sam McCoach, who sources all her kilts and knits in Scotland (she has a Le Kilt Mini collection for girls, too). Or Nicholas Daley, the young menswear designer with dual Scottish and Jamaican heritage, who uses British tweeds and hat-makers. Or Richard Malone, the Irish designer in London whose fabulously cut collections – he has many customers in the art world – has made a point of forging long-standing relationships with women weavers in Tamil Nadu; thus supporting a skilled community in India. A lively relationship has sprung up between K-Pop stars and young British menswear brands in London. ‘Young music people, actors and actresses in Seoul know all about emerging British designers,’ says the Korean fashion consultant Inhae Yeo, whose website Oikonomos.co.uk tracks this growing two-way relationship. ‘Often they contact the designers via Instagram. They want original things to wear on stage and in video. Their style is hugely influential with young people throughout Asia.’

There are many small British businesses that rely on this growing connection with informed and increasingly adventurous Asian customers. Caroline Rush, CEO of the British Fashion Council, observes, ‘We know that the new Chinese luxury consumer is curious about new, relevant, thought-leading businesses, a hallmark of British Fashion Talent. One common thread is that the customer is moving away from logo-led product towards more subtle, educated choices – we’re seeing this in both the discovery of formal wear and the tradition of bespoke tailoring, and the embracing of designer menswear brands like JW Anderson, Craig Green and A-Cold-Wall.’

Strength in Integrity

In the end, Britain has three incredibly strong assets which it may not even wholly recognise itself. One: the culture of design and individuality which comes directly from its art schools – a tradition within which copying is looked down on, and self-expression and innovation prioritised. Two: the strength of its heritage in tailoring and other crafts upholding unwavering standards of excellence. Three: the fact that people love to visit Britain. While it’s important to seize the opportunity to sell globally, it’s equally vital for British brands to stay right where they are, to identify as who they are, play up the things people like about us, rather than getting lost in oceans of anonymous products. If there were proof needed, look at the phenomenal success of Bicester Village – a shopping destination which magnetises thousands of Chinese tourists each week. Bicester, in the Oxfordshire countryside, is a one-stop must for foreign visitors on their way to see grand country houses and museums (as well as being a short 45-minute train ride from London for homegrown fashion fanatics). Bicester carries all the big international fashion labels you can think of, from Gucci to Saint Laurent. But in the mix there is – and has to be – a roster of exactly the kind of British designers new customers are coming to discover – Bamford, Barbour, Rupert Sanderson, Hackett, and so on.

With its strengths in design integrity, originality and its essentially welcoming nature, a Britain on its own does still have masses of points which outsiders looking in do really like and enjoy. If only we would realise and celebrate it more as a country, we might really get somewhere.

Sarah Mower is chief critic of Voguerunway.com. Her recent book London Uprising: Fifty Designers, One City (Phaidon) documents the British designer landscape.

Buy The Book: Great British Brands 2019, The International Edition