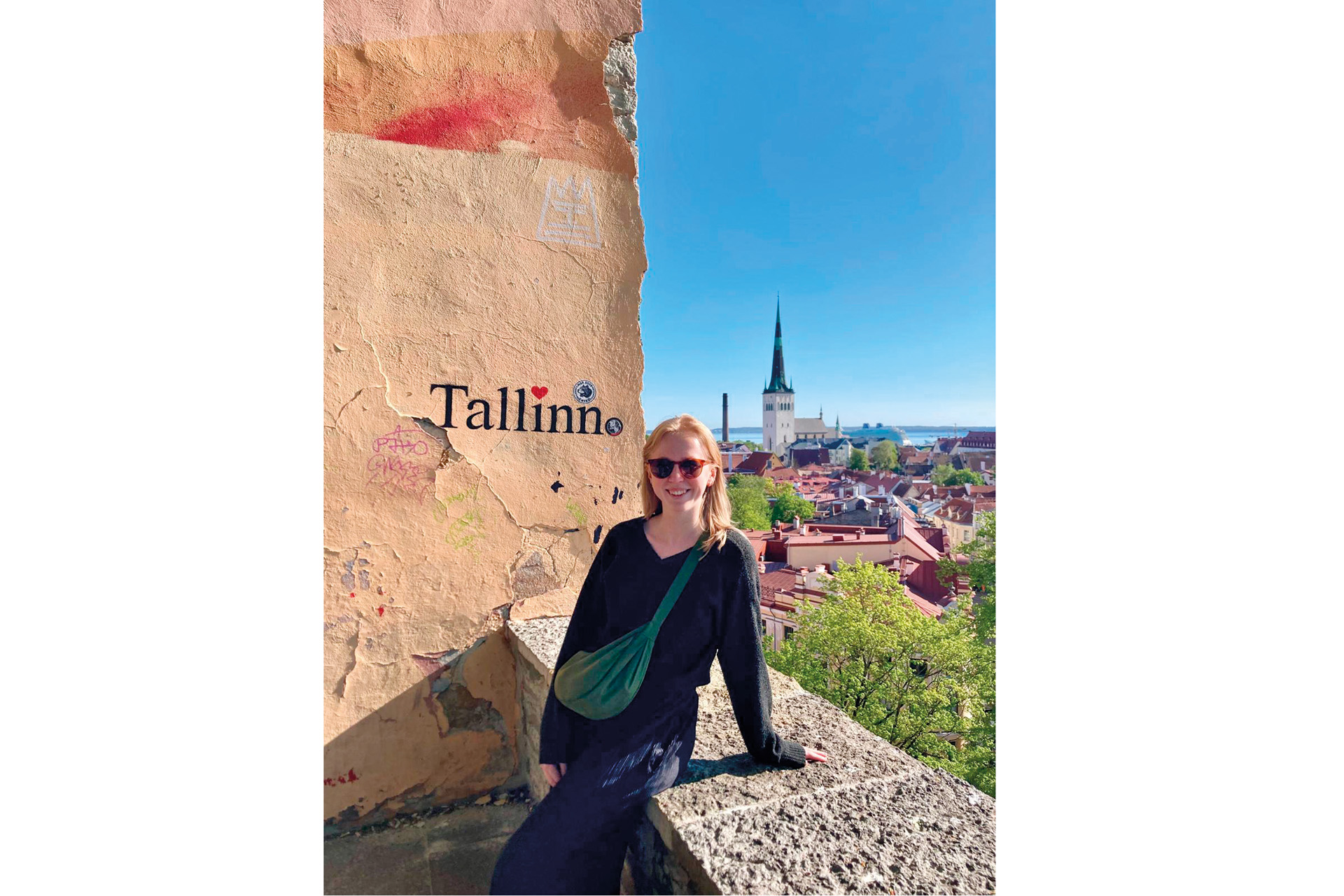

Here’s Why You Should Skip The Med & Head To The Baltics This Summer

By

9 months ago

As temperatures soar in southern Europe, it's time to look north

Olivia Emily discovers history, high-tech cities, and liquid health in a tour of the Baltics.

C&TH Guide To Responsible Tourism

Are The Baltics The New Mediterranean?

Last August, I spent two weeks dodging 35°C heat in Italy. I gazed longingly at water fountains bursting from baking streets across the nation’s ancient northern cities, slept with a wet flannel on my forehead, and lapped melting gelato from my hands as it spilled from the cone.

Flash forward to May 2024, and I’m experiencing much the same thing: gazing at picturesque palaces and town halls from sun-soaked courtyards, wise enough this year, at least, to select a tub for my ice cream. This time, however, I’m much further north, enjoying the wide leafy streets of Vilnius in Lithuania, a city I come to think of as the East London of the Baltics thanks to the concrete ex-Soviet housing blocks lining the highways, marvellous street art to be uncovered around every corner, and leafy canal cutting through it all.

This is the final city on our whistle-stop tour of the Baltics, a trip I’ve taken with Exodus Travels that stretches for 12 days and absorbs the best cultural and historical sights, sites and oddities the three Baltic nations have to offer. For the uninitiated, that’s Estonia (where we begin), Latvia and Lithuania (where we end).

The old fishing village of Käsmu, Estonia

To be shown around a new country by a local is always fulfilling, but to discover the Baltics as they are today guided by people who remember them as they were not so long ago – quashed, totalitarian – is staggering. As we move freely through the three nations, which gained independence from the USSR between 1990-1991, Marius and Andrius enrich each spot with their experiences: that tall building over there was Tallinn’s only hotel for international visitors – and it was bugged top to bottom; that TV tower is Vilnius’ – and Lithuania’s – tallest structure, and we still only had two channels growing up; in the Baltics, alcohol is pure liquid health, they say, pouring another round of Riga Black Balsam (a liquor not dissimilar to Jägermeister, used by a pharmacist to treat Catherine the Great’s sickness – or so the story goes). Perhaps their most bewildering admission to me, is that they grew up without Christmas. ‘My kids love it, but I still prefer New Year,’ Marius tells me.

Here in Vilnius, a baroque city, there is enough history to feed a curious mind for days. Take Kablys, an old cinema that used to screen films preceded by 15 minutes of Soviet propaganda, now a nightclub; or the harrowingly beautiful streets that once formed the Vilna Ghetto under the Nazi Reichskommissariat Ostland, where 40,000 Jewish people were murdered in under two years (1941-43). Or the Jewish Cultural Centre with its haunting exhibition and tiny hide-out, once inhabited by eight Jewish people with no other choice; and, stretching further into history, the Bastion of the Vilnius Defence Wall, which details the Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s storied history (it was briefly, in the 14th century, the largest nation in Europe).

Just outside the city, there’s even more to absorb. UNESCO World Heritage site Kernavė awaits, the first capital of Lithuania dating to the ninth century. The ancient city burned down in 1390, around the end of the Crusades (a pagan nation, the ancient Lithuanians were naturally thought devilish by members of the church); what remains are disconcerting artificial hills, originally built for protection, grassed over yet still unnaturally straight-edged all these years later. Perfect for hikers and nature enthusiasts, buttercups and dandelions spring up under step, flighty deer hide among the slender tree branches, and slow worms meander along dust paths, all soundtracked by the gushing River Neris.

Over 100,000 crosses are placed at the (well) named Hill of Crosses, Lithuania

Further south, we light on Trakai, an ancient island castle that once formed the centre of a fortress. And further north, just across the border from Latvia, is proof that Lithuania’s Soviet atheism really is ancient history (as, too, is its paganism): the surreal Hill of Crosses stands atop a hillock in the middle of nowhere, a place of Christian pilgrimage and a modern marker of peace, boasting more than 100,000 wooden crosses, creating a fantastical folk art installation.

We journey between these spots by spacious minibus, traversing straight flat roads flanked by fields spotted with endless dandelions and forests of spindly trees grappling to be the tallest. Bus stops appear and disappear at even intervals, some incongruously decorative relics of Soviet rule. Other cars are infrequent, traffic a rarity, cows occasional and cranes sporadic, picking through the grass with their spindly legs and pointed beaks.

One day, we pass through Gauja, Latvia’s largest and oldest national park criss-crossed by defunct train tracks and dotted with cows, subsistence farms, more bus stops, and wooden houses perched beside small lakes, its bubbling river cutting through the middle. Here, we have the rare opportunity to descend nine metres into an ex-Soviet bunker, built beneath a hospital from 1970-80 by non-Russian-speaking Estonians to ensure it remained top secret. At 2,000 sq/m, it is larger than Hitler’s, with power generated by two old tank engines, housing up to 250 people for three months – albeit in very close quarters. We’re shown gas masks, and Marius dons one in record speed, muscle memory from going to school with the ever-looming threat of nuclear war.

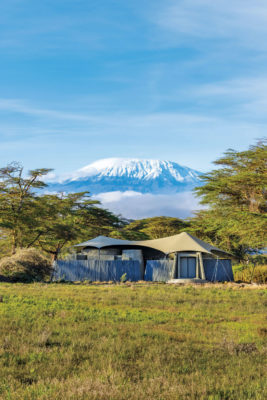

Tallinn old town is completely separate from the new town

The Baltic capital cities – Tallinn, Riga and Vilnius – have experienced an uptick in tourists recently, almost back at their pre-pandemic levels despite Russian visitors, historically their largest market, being banned. Today, Finns have taken the lead. It’s these just-outside-the-city spots that are attracting more attention, with city breakers and hiking tourists alike visiting in droves. Likewise, Baltic beach resorts – such as Estonia’s manicured summer village of Käsmu, with pristine gardens opening out into the Gulf of Finland, or Latvia’s beach town of Jūrmala, where 19th-century fishing villages have made way for wooden holiday homes – will surely soon benefit, boasting thick bands of soft sand lapped up by gentle waves.

The most popular of the three capitals is Riga, a terracotta town founded by Bishop Albert in 1201, capitalising on Christmas market tourism in recent years. Home to more than 800 wedding-cake-like Jugendstil buildings (the German equivalent to Art Nouveau), we admire the architecture and weave through winding alleys, pausing for coffee on elegant boulevards. There’s a discomfort fizzing beneath the surface, especially when we light on the Russian Embassy papered with protest posters and Ukrainian flags. ‘We’re sensitive,’ Marius tells us, ‘with everything happening in Ukraine. Are we next?’ Outside government buildings, flower beds are striped with yellow and blue blooms.

Here, with such a harrowing history of occupation, Russia’s war on Ukraine understandably hits close to home: Estonia and Latvia are bordered by Russia to the east, while Kaliningrad is squashed between Lithuania and Poland to the west. So is it unsafe? Not according to the Global Peace Index – in which all three nations rank higher than the UK. Only occasionally do we see tanks rolling out east, NATO demonstrating its power.

Swedish Gate in old town Riga, Latvia

It’s a similar story in Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, perched on the north coast an 80km ferry ride from Helsinki. During USSR rule, the city’s beaches would be raked each night so law enforcers could capture anyone trying to escape; the Embassy, again, reflects an Estonian resistance to Russia.

In May, it’s a consistent 22°C-ish, occasionally reaching a lovely 26°C, perfect for city exploration – and getting hotter every year. As I soak it up from that sun trap Vilnius courtyard, I manage to eat my ice cream in the knick of time.

BOOK IT

Exodus Adventure Travels’ 12-day guided Discover the Baltics trip, from £1,699pp, excluding flights. exodus.co.uk

Olivia’s return flights had a carbon footprint of 584kg CO2e. ecollectivecarbon.com