Extract From The Flow: Rivers, Water and Wildness by Amy Jane Beer

By

3 years ago

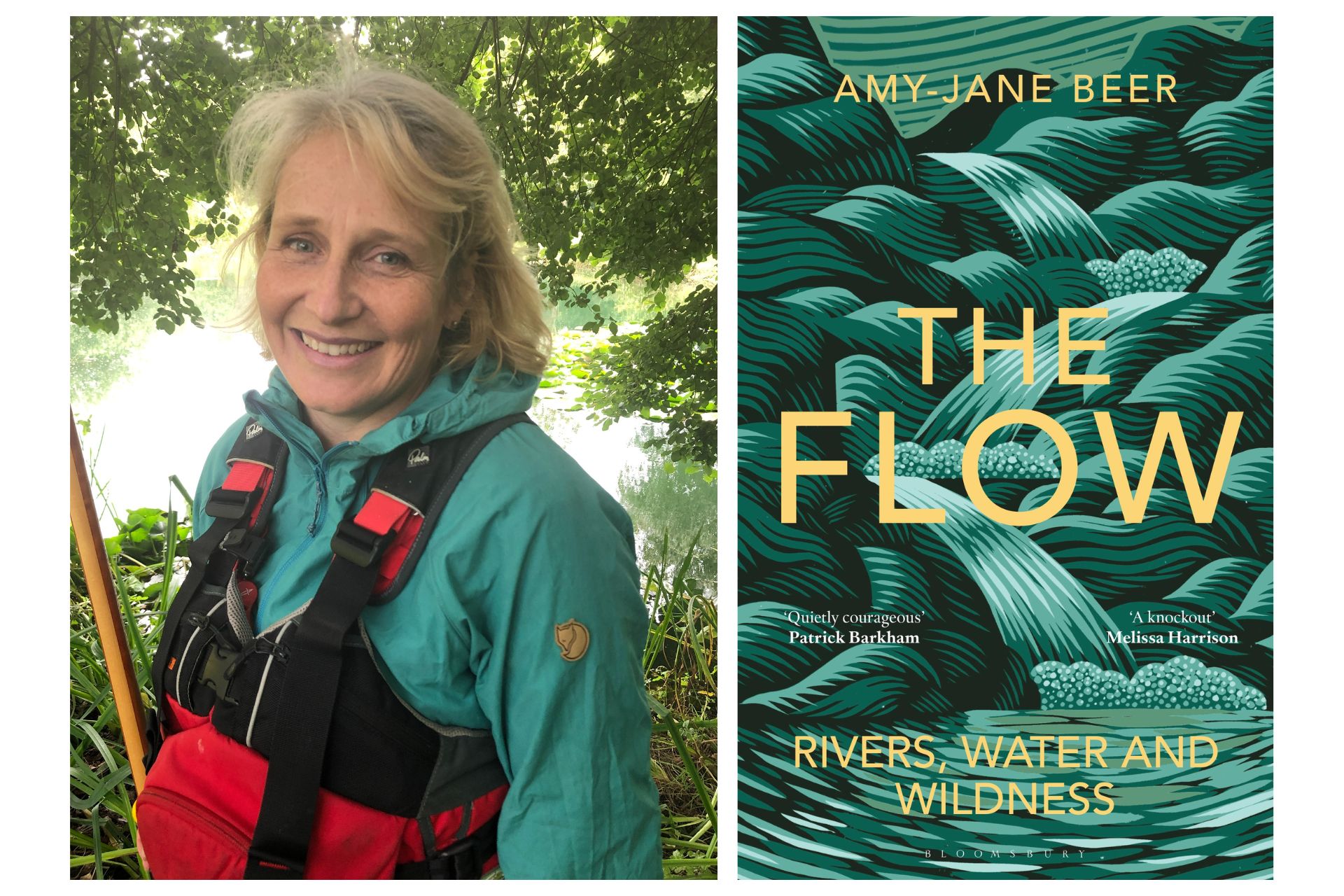

Appreciating our natural surroundings – especially when they’re at their wettest and wildest – isn’t always easy. But nature has a lot to teach us, and Amy-Jane Beer explores this in her new book, The Flow: Rivers, Water and Wildness, out now. Amy is a biologist, naturalist, writer, and campaigner, and The Flow is powerfully immersive nature writing about finding strength, solace and wonder in the natural world.

Best Podcasts About the Environment

Extract From The Flow: Rivers, Water and Wildness

It’s almost four o’clock when I park at the trail head – I only have two hours of useable light, so I pack quickly, call home while I still have phone signal, and walk.

By four-forty the sun is dipping below the forested whaleback hill to my right, while the bald high flanks of Càrn Bàn Mòr and Meall Dubhag, western outriders of the Cairngorm massif, are still bathed in golden light. A sign at a gate welcomes me to the Glenfeshie estate, asks me to keep the gate shut to prevent sheep from getting in. It also warns that the bridge from Carnachuin, marked on older maps, was washed away in a spate some years ago.

Almost immediately I have a ford to cross. Coming straight after the warning about the missing bridge it sets the tone. This is not somewhere you can expect help in crossing water whose flow is a dominant force here and it’s up to you to negotiate it as best you can. The water overtops my boots and I think ruefully that my feet might not be dry again until tomorrow night.

Close to the path up ahead I can see a what looks like a short cane with a scrap of bright red surveyors’ tape at the top, fluttering in the breeze. I’m almost on top of it when I realise it’s not a cane but a tiny tree. A stripling rowan, beside a pool of black peaty water, it’s scarlet leaves so bright they seem to shout. And it strikes me suddenly that there is something to shout about. Here I am! It says. I’ve not been nibbled off! And now I’ve noticed this one, I start to see others, mostly pine and birch, some seven feet tall, some just a few inches. But the more I look, the more I see and after another few minutes’ walking, they are everywhere.

The few people I’ve seen are all heading the other way: a couple of mountain bikers and three cheerful young nuns, the white of their wimples gleaming in low sun. That was half an hour ago, and as I walk on, I’m aware of a swelling sense of solitude, but not of loneliness. In fact the opposite. I have a profound sense of being at home. I feel welcome.

I linger on the bridge, which is now the last (or the first) on the Feshie, not because I want to cross, but because the view upstream is a stonker. The river, it seems, is a restless inhabitant of a huge, generous space, with a penchant for moving the furniture, knocking down walls. Everywhere are signs of recent watery renovations: gravel banks and islands, boulder gardens and land slips. It’s dynamic, untidy, wild in the original sense, of a willed thing.

The path winds among trees for a stretch and I’m surprised to see a temporary-looking laminated cardboard sign: Steep Drop Ahead. It seems a strange kind of warning, given the general nature of the place, where surely steep drops are to be expected, but as I round the bend and descend a few rocky steps, the path disappears. The ‘steep drop’ is in fact a ten-metre cliff of recently exposed glacial deposits with the river clawing at the plum-pudding mix of ancient silts, gravels and boulders its base. Steep drop? Bloody hell! I chuckle at the understatement and find the way others have obviously climbed down. Immediately there is another obstacle: a gushing burn, which my map identifies as the Allt Garbhlach, ripping down a cleft in the side of the glen, with an apron of variably striated, washed-out boulders in humbug and bonbon shades of black, white, pink and grey. There’s no bridge, at least no man-made one, but a huge multi-stemmed pine has toppled across the torrent, as generous in death as in life, offering a way across. I climb slowly and carefully along the branches. There are thousands, no, hundreds of thousands of holes in the bark where insects have emerged, and woodpeckers have probed and excavated. It feels like an unearned intimacy, a trespass into the private anatomy of the tree, and I find myself begging pardon of this uprooted matriarch and, once safely across, I pat the trunk.

‘Thank you, Granny Pine.’

I scramble up another heavily eroded bank into an area of much younger pines, a plantation judging by their uniformity, where the path glows rufous with dead needles through a vivid green carpet of knee-deep bilberry and moss. It’s very quiet in amongst the trees after the pummelling, boulder-rattling rush of the Allt Garbhlach, but water is running here too – a soft trickling, tickling sound from several sinuous, crystal-clear watercourses winding though the moss, each just a few inches across, a baby step. There’s heather too, flowers still with a faint blush of ashy pink. The trees have craggy lichenous bark around their ankles and a natural ombre from grey to mauve above head height, then higher up still they flush a gorgeous flaky red, emphasized by the low sun. And here too there are tiny new trees, mostly rowans, presumably sprouted from seeds defecated by birds. They flicker gold and lemon and red, like candles in the green.

The Flow: Rivers, Water and Wildness by Amy-Jane Beer is published by Bloomsbury Wildlife 4th August (Hardback: £18.99). C&TH readers get 25 per cent off until 31 October. Purchase via the Bloomsbury website and enter the code CTH25 at the checkout. bloomsbury.com

Featured image: Looking out over the Loch A’an deep in the Cairngorm National Park, Scotland (Getty)

READ MORE

Must Read Books on Sustainability / Books Everyone Should Read at Least Once